Nocturnal enuresis, or bedwetting, refers to intermittent incontinence during sleep in children aged 5 years or over.1 It is a common condition which may have long-term psychological consequences, but there are still many misconceptions amongst patients, families and physicians regarding the most appropriate management of this condition.1

In 2020, the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) published an updated standardisation document on the management and treatment of bedwetting. It provides guidelines for the range of healthcare professionals supporting children with enuresis, and is intended to be clinically useful for the non-expert.1 These, and other relevant updates on why, when and how to treat bedwetting are shared here.

Why, when and how to treat bedwetting

Why?

As we have seen in some of our other blogs, posted here and here, the social, emotional and sleep-related impact of bedwetting can be incredibly hard for patients and their families to deal with.

In most cases, bedwetting can be treated – either in primary care or with referral to specialists in more complex cases. There is therefore no need for children to continue to suffer indefinitely with the embarrassment, damage to self-esteem and other challenges associated with enuresis. We, as healthcare practitioners, have the capacity to offer help to these patients and proactively improve their condition with a tailored management strategy, based on a thorough assessment of the aetiology of the condition and an understanding of each family’s needs.

Data show that proactive treatment of enuresis is associated with better health-related quality of life, as is partial or total response to treatment.2 There are also data to suggest that effective treatment of enuresis may improve daytime behaviour and executive function, via improvements in sleep.3 A history of bedwetting is associated with nocturia (waking to void during the night) in later life4 – further research is needed to fully understand this transition and whether treatment of enuresis can help to prevent later nocturia.

When?

Active therapy for bedwetting is recommended from around the age of 55 or 6 years,1 and it is generally advised that treatment should be introduced when the child is old enough to be bothered by the condition.1

However, it has been reported that the majority of parents are unaware of effective treatments for bedwetting, and only around half would seek medical care for the condition.6 Some families attempt to use home behavioural therapies (e.g. limiting fluid intake before bed, and lifting [i.e. taking the sleeping child from bed to the toilet during the night]), with limited success.6,7 Some children and also parents may feel embarrassed to discuss the problem with a clinician, and it may therefore be necessary for the clinician (be they a nurse, GP or paediatrician) to instigate the discussion during routine or other appointments to offer the opportunity for families to seek professional help.8

How?

The following summarises the latest recommendations on the evaluation and management of patients with enuresis – for comprehensive guidance please see the full publication.1

INITIAL EVALUATION

The initial evaluation should help the clinician to detect any ‘warning signs’ of important underlying conditions that need to be addressed as a priority

- Medical history

- Talk to the child, not just the parent, to establish relevant information relating to bedwetting, general health, daytime voiding habits, urinary tract infections, bowel habits, sleep problems, behavioural issues and any previous treatment

- The ICCS clinical guidelines can be used as a checklist for the evaluation9

- Examinations

- A physical examination is generally not required, unless there are warning signs in the medical history

- A standard voiding chart (assessing incontinence [night and day] for at least one week and daytime voided volumes and fluid intake for at least two days1) is recommended for all children, and essential for those with signs of non-monosymptomatic enuresis (i.e. daytime lower urinary tract symptoms [LUTS])

- A urine dipstick test for glucosuria and leukocytes should be undertaken in cases with secondary enuresis, daytime LUTS, and any relevant warning signs

- Urodynamic investigations are only recommended when there are voiding difficulties

- If there is any suspicion of constipation, two weeks of bowel diaries should be requested

GENERAL ADVICE TO FAMILIES

- All families should be reassured that bedwetting is nobody’s fault – this impression is still surprisingly pervasive.

- Clinicians should tell the family that help is available and that they will not give up until they succeed1

- Families’ current beliefs or practices in relation to bedwetting causes and treatments should be addressed – many common approaches (such as restricting fluid intake in the day, and waking the child to go to the toilet at night) are not medically motivated, evidence-based or curative1,7

- Bedwetting is a medical condition.

- If your child is at least 5 years old, discuss the bedwetting problem with your family doctor or their school nurse.

- Do not blame or punish your child. Bedwetting is not your child’s fault.

- Bedwetting is not caused by anything you or your child has done or is doing that is wrong.

- Understand that bedwetting is a problem that can be solved in most patients.

- Do not wake your child at night to go to the toilet, but do take them if they wake up on their own.

- Encourage your child to drink water-based fluids regularly throughout the day.

- Be supportive of your child. Reward your child by giving them compliments for any effort they make with things they can control such as drinking more in the day or going to the toilet just before going to sleep, not for the result of any dry beds.

- Let your child use diapers/pull-ups to increase comfort and to decrease stress, if this helps you and them to manage the problem while you wait for assessment and treatment.

INITIAL TREATMENT

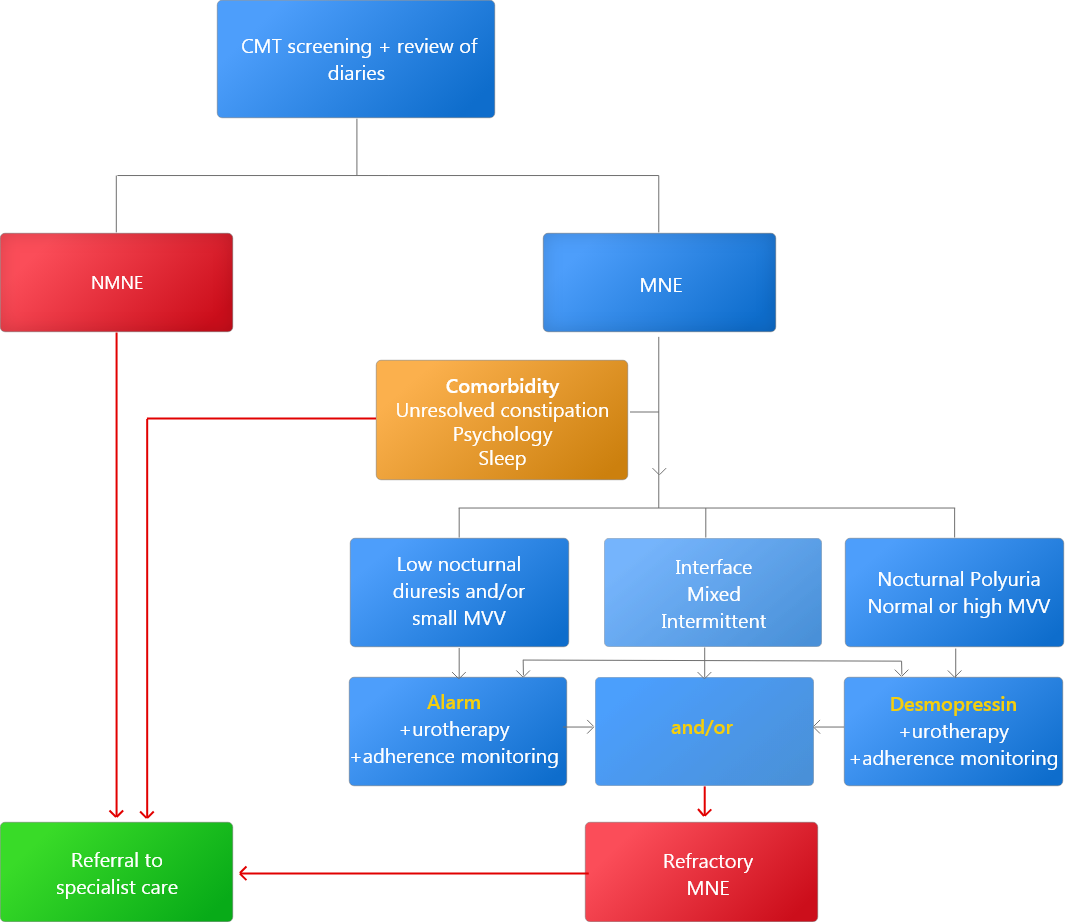

Diagnosis and management flowchart9

Urotherapy: advice regarding drinking schedule and toilet posture

CMT, clinical management tool; MNE, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; MVV, maximum voided volume; NMNE, non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis;

NON-MONOSYMPTOMATIC NOCTURNAL ENURESIS

- Concomitant daytime LUTS indicate that uninhibited detrusor contractions (overactive bladder) probably have a pathogenic role (affecting treatment choice) and that somatic (e.g. constipation) or psychiatric comorbidities are more likely – these should be screened for and addressed as appropriate

- The consensus is that any constipation should be treated first, and that daytime LUTS should be treated before the nocturnal enuresis – especially if daytime LUTS are a major problem. If daytime LUTS are minor, initiating anti-enuretic therapy at the same time may be appropriate

MONOSYMPTOMATIC NOCTURNAL ENURESIS

- There are two well-established first-line treatments for enuresis, both with evidence level 1a: the enuresis alarm and desmopressin

- Selection of first-line therapy should be based on voiding charts (if performed), and family and child preference/motivation

- If voiding charts indicate that the child has nocturnal polyuria (overproduction of urine at night), and normal daytime voided volumes, desmopressin may be the most appropriate first choice

- If voiding charts indicate small voided volumes and normal nocturnal urine output, alarm may be the most appropriate first choice

- In either case, parent and child preference should be considered, and ongoing support should be provided to promote adherence

- Alarm treatment, which activates an arousal stimulus in response to a wet bed or clothes, has a success rate of 50–70%10 but a high dropout rate11; successful treatment represents cure in many12

- Desmopressin is a vasopressin analogue that concentrates the urine, reducing the volume of urine produced at night so that it can be contained within the bladder until morning

- Approximately one third of patients have a full response, one third partially respond, and another third experience no benefit

- If the child responds to therapy, they may choose to take it every evening or only on “important nights”

- Combination therapy may benefit children with low voided volumes and high nocturnal urinary production, or those who have sub-optimal response to one treatment

FOLLOW UP

Families should be proactively followed up so that healthcare professionals can monitor the success of treatment and provide alternative strategies if required – some children will not respond to either first-line therapy, and should be referred for specialist evaluation (see article on refractory cases)

In certain circumstances (e.g. during the COVID pandemic or in rural areas), follow up of patients by telemedicine may be useful,13 but in general, and certainly for initial evaluation, face-to-face consultations are recommended.

References

- Nevéus T, Fonseca E, Franco I, et al. Management and treatment of nocturnal enuresis-an updated standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16(1):10-19. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.12.020

- Iscan B, Ozkayın N. Evaluation of health-related quality of life and affecting factors in child with enuresis. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16(2):195.e1-195.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.12.018

- Van Herzeele C, Dhondt K, Roels SP, et al. Desmopressin (melt) therapy in children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis and nocturnal polyuria results in improved neuropsychological functioning and sleep. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(9):1477-1484. doi:10.1007/s00467-016-3351-3

- Gong S, Khosla L, Gong F, et al. Transition from Childhood Nocturnal Enuresis to Adult Nocturia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Res Rep Urol. 2021;13:823-832. doi:10.2147/RRU.S302843

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bedwetting in under 19s, Clinical Guideline CG111. Published 2010. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg111

- Schlomer B, Rodriguez E, Weiss D, Copp H. Parental beliefs about nocturnal enuresis causes, treatments, and the need to seek professional medical care. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9(6 Pt B):1043-1048. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.02.013

- Grzeda MT, Heron J, Tilling K, Wright A, Joinson C. Examining the effectiveness of parental strategies to overcome bedwetting: an observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e016749. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016749

- Cederblad M, Nevéus T, Åhman A, Österlund Efraimsson E, Sarkadi A. “Nobody asked us if we needed help”: Swedish parents experiences of enuresis. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10(1):74-79. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.06.006

- Vande Walle J, Rittig S, Tekgül S, et al. Enuresis: practical guidelines for primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(660):328-329. doi:10.3399/bjgp17X691337

- Glazener CM, Evans JH, Peto RE. Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(2). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002911.pub2

- Evans J, Malmsten B, Maddocks A, Popli HS, Lottmann H. Randomized comparison of long-term desmopressin and alarm treatment for bedwetting. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2011;7(1):21-29. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.04.018

- Kosilov KV, Geltser BI, Loparev SA, et al. The optimal duration of alarm therapy use in children with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2018;14(5):447.e1-447.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.03.021

- Smith E, Cline J, Patel A, Zamilpa I, Canon S. Telemedicine Versus Traditional for Follow-Up Evaluation of Enuresis. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(2):213-217. doi:10.1089/tmj.2019.0297