Treatment resistance

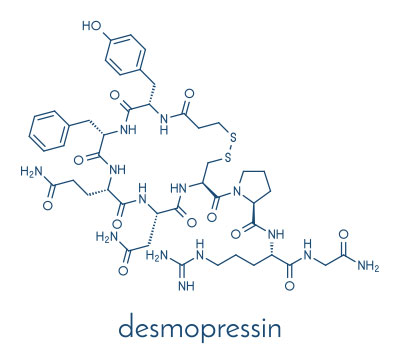

Although the enuresis alarm and desmopressin are effective, evidence-based first-line strategies to tackle bedwetting, it is estimated that up to 50% of children with enuresis are resistant to these treatments.1 However, there is still much that can be done to improve the condition in these individuals. Indeed, a relatively large proportion of patients (approximately one third) who are believed to be resistant to desmopressin, are subsequently successfully treated with the drug at specialist centres.2

There are many potential reasons for treatment resistance or apparent treatment resistance – some more easily addressed than others. In cases where there has been limited or no response to first-line treatment, referral to a specialist is usually required.

The most common reasons for non-response or partial response to first-line treatment3

Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis or non-monosymptomatic enuresis

Non-monosymptomatic enuresis may sometimes be missed in the initial evaluation. For example, daytime lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) may be masked by low fluid intake. A repeat extended evaluation should be performed with focus on a detailed history of LUTS including daytime overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms and constipation, as well as voiding and fluid intake diaries, to identify daytime LUTS, urine volumes and levels of fluid intake. This will help to clarify whether enuresis is indeed monosymptomatic or non-monosymptomatic.

Adherence

High levels of adherence are required for both the alarm and desmopressin therapy. This not only includes using desmopressin or alarm each day, but also adhering to administration instructions such as voiding before bedtime and reducing fluid intake from one hour before desmopressin administration. Where practical, children should take desmopressin at least one hour before the final void of the day.4

Comorbidities/mixed aetiology

There are many factors that may contribute to enuresis, such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, sleep problems, constipation, or side effects of other drugs – these should be identified and addressed where necessary.

As discussed in another blog, psychological comorbidities such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism spectrum disorder are associated with enuresis and can also make enuresis more challenging to treat. These conditions should be recognised and treated as appropriate, which may help to increase effectiveness of enuresis therapy (e.g. through greater adherence or ability to follow instructions).

Combined aetiology of enuresis (low voided volumes and high nocturnal urine production) indicates a need for combined therapy (alarm and desmopressin). Other combinations of therapy, such as with anticholinergics, may also be appropriate in specific cases after specialist evaluation.4

Rare types of enuresis

There are some rare types of enuresis that may not respond to first-line therapy. For example, nocturnal polyuria that does not respond to desmopressin may be attributable to high urinary osmolality at night – e.g. due to an increased solute load (usually sodium). This may be due to nutritional intake or abnormalities of circadian rhythms and sleep patterns.3

What next?

For more detailed information on possible causes of treatment resistance and strategies to overcome resistance, please see relevant publications by Vande Walle & Rittig3, Kamperis et al.4 and Nevéus et al.5

It has been reported that the more treatment failures a patient experiences, the greater the reduction in their self-esteem.6 Below, we have compiled a list of advice that clinicians can give to children and families using alarm and desmopressin that may help them to achieve a good response to first-line treatment. It should be noted that alarm treatment should not be prescribed where there are safeguarding concerns.

Other useful resources are available at:

- https://www.bbuk.org.uk/?s=bedwetting&searchsubmit=Search

- https://www.bbuk.org.uk/bladder-resources/

Suggested advice to give to patients and families to increase the success of treatment

- Only start your child’s alarm treatment when they have practical and emotional support available, or if they are able to manage treatment independently

- Do not start alarm treatment in a stressful period (e.g. divorce, moving house, exams)

- The ideal period to start alarm treatment is a school holiday, to reduce the impact of tiredness during the first days of treatment

- Motivate and support your child by noticing efforts they make and by giving compliments and providing support and encouragement

- Alarms can take several weeks to be effective. Smaller voids in the underwear and an extended time until the first bedwetting episode are early signs of success

- Be adherent – follow the instructions given to you by your healthcare professional

Encourage your child to:

- Drink lots of water during the day

- Always pee before settling to sleep

- Not read or play in bed after the last void and before sleep. Lights should be turned out immediately.

- Fluid intake is important:

- Drink lots of water during the day

- Do not drink in the last hour before taking desmopressin

- Do not drink during the night

- Avoid eating in the last two hours before bedtime, particularly if using the tablet formulation of desmopressin. This is because the presence of food in the stomach may reduce the absorption and so the effectiveness of the desmopressin

- Always pee before settling to sleep

- Do not read or play in bed after the last void and before sleep. Lights should be turned out immediately

- Make sure you take your medication as instructed by your family doctor

- Do not take desmopressin on nights where you have had a drink within the last hour before going to sleep, or when you are ill with diarrhoea, vomiting or a raised temperature

References

- Caldwell PHY, Lim M, Nankivell G. An interprofessional approach to managing children with treatment-resistant enuresis: an educational review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(10):1663-1670. doi:10.1007/s00467-017-3830-1

- Rittig N, Hagstroem S, Mahler B, et al. Outcome of a standardized approach to childhood urinary symptoms-long-term follow-up of 720 patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33(5):475-481. doi:10.1002/nau.22447

- Vande Walle J, Rittig S. Voiding Disorders in Children. In: Geary DF, Schaefer F, eds. Pediatric Kidney Disease. Springer; 2016:1193-1220. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-52972-0_45

- Kamperis K, Van Herzeele C, Rittig S, Vande Walle J. Optimizing response to desmopressin in patients with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(2):217-226. doi:10.1007/s00467-016-3376-7

- Nevéus T, Fonseca E, Franco I, et al. Management and treatment of nocturnal enuresis-an updated standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16(1):10-19. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.12.020

- Theunis M, Hoecke EV, Paesbrugge S, Hoebeke P, Walle JV. Self-Image and Performance in Children with Nocturnal Enuresis. European Urology. 2002;41(6):660-667. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00127-6